Guest Author Louise Heathwaite

Professor Louise Heathwaite is Pro-Vice-Chancellor for Research and Enterprise at Lancaster University and council member of the UK Research and Innovation Natural Environment Research Council. She is on the advisory group of the Industrial Strategy Challenge Fund Transforming Food Production and has previously served as Chief Scientific Adviser to the Scottish Government on Rural Affairs, Food and Environment and as a member of the Defra Science Advisory Council. She is an expert in agricultural pollution and water quality.

In this blog, Professor Heathwaite discusses how land use location data could help us make more joined-up decisions about land use to avert a collision course with our most valuable asset.

What is land for?

A number of years ago, I was part of a small expert group on Land Use Futures advising the Government Office for Science. The underpinning challenge we were tasked with - what is land for? I don’t believe we resolved this challenge despite our 325 page report and consulting with over 300 leading experts and policy advisers. Three things constrained us:

(1) The myriad of interests intent on defining the purpose of ‘land’ from their particular - but not necessarily shared, perspective.

(2) The lack of a pervasive UK strategy or even a joined-up conversation about land use.

(3) The constraints imposed on that conversation by limited data at relevant scales (both in space and time) and restricted dataset interoperability – the data didn’t talk.

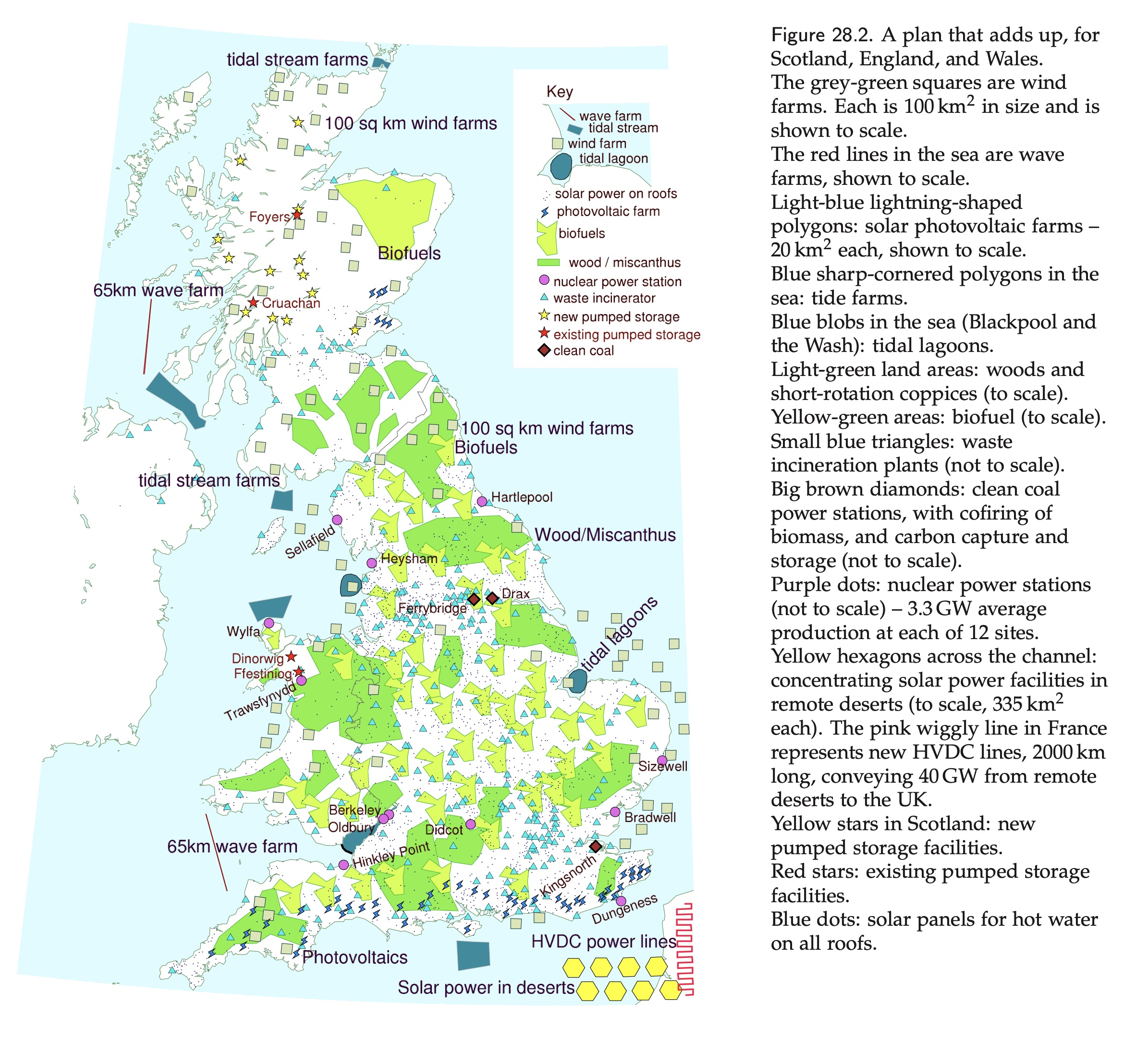

The map below is a good example of why we need that joined-up conversation. It was put together by Sir David Mackay in a wonderful book published in 2008 to explain, amongst other things, the land area we would need to dedicate to renewable energy production if we were serious about it being our primary source of energy. The area needed does not leave much space for other uses, unless one regards e.g., wood as both a source of energy and a carbon sink - the multifunctional land use challenge currently being explored by the Royal Society.

The bigger picture

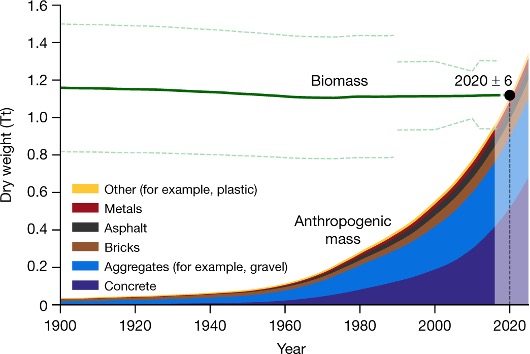

We humans have just crossed an important threshold. On a mass basis, our planet has more human-made ‘stuff’ like buildings and infrastructure for transport, water, energy and digital than all living things as the graph below shows. Human-made materials dominate the way we use land: one only has to look at the National Infrastructure Assessment (2018) to see this. Our infrastructure choices impact the environment, often degrading our natural capital e.g. removing biomass such as forests and damaging soil health. But now we want that same land to do more for us to sustain our existence e.g. through carbon sequestration and habitat creation. Without a joined-up discussion, we are on a collision course with the UK’s most valuable asset at the centre. This blog looks at how land use location data could help us make more joined-up decisions to help avert that collision.

Global human-made mass exceeds all living biomass. The green line shows the total weight of biomass (dashed green lines, ±1 s.d.). Anthropogenic mass weight is shown in the area chart for the mass of six major categories accumulated that year. Nature 588, 442-444

Why land use is a tricky challenge

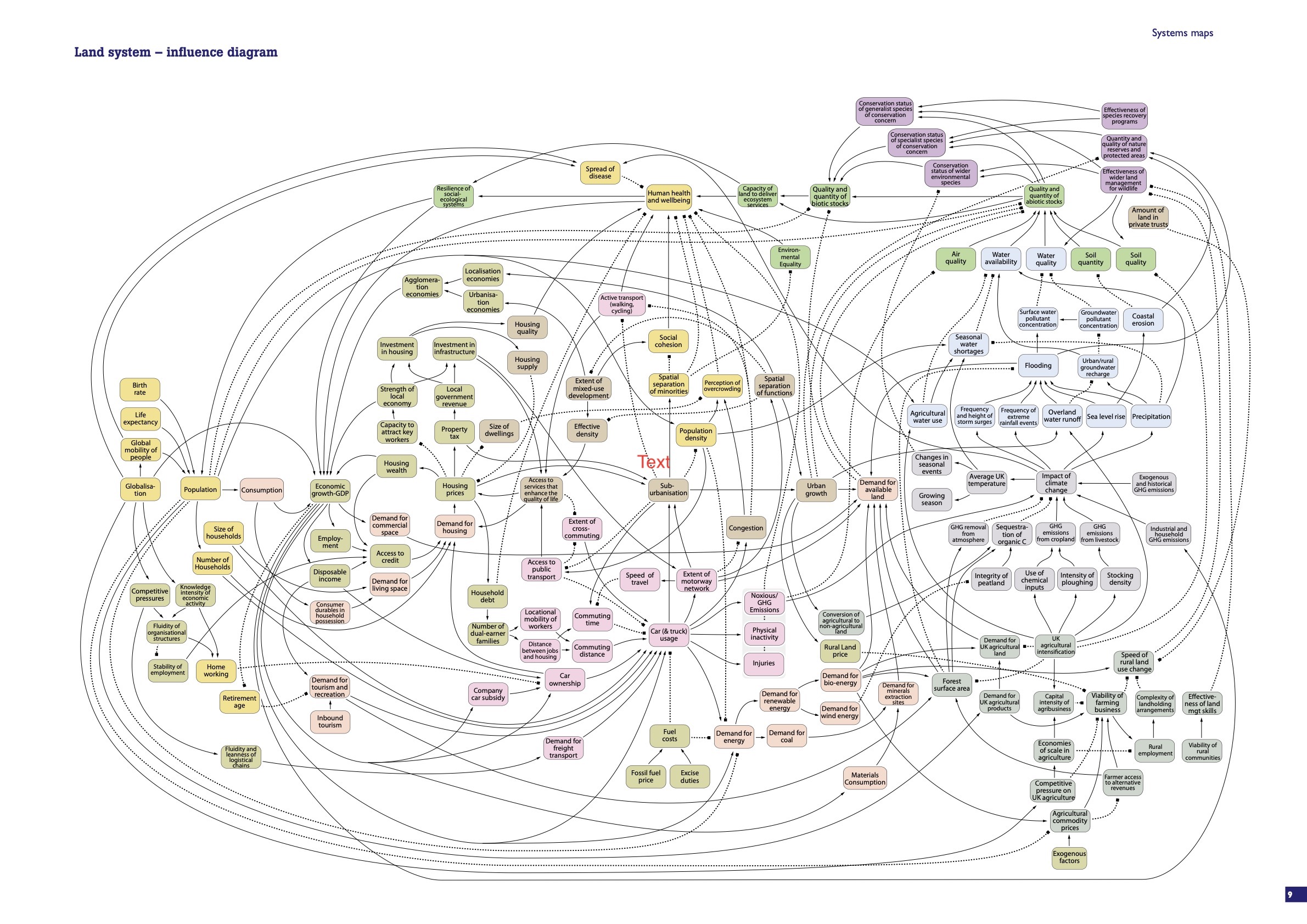

We want a lot of things from land. As a consequence the value of land varies spatially, and land use in one part of the land system impacts on other parts. The figure below simply serves to illustrate the number and complexity of influences in the land system.

To understand the land system, it is not enough to look simply at land cover: this only provides data about where, not data about why (purpose) and what (impact). On the ‘what’ - I have spent much of my academic career showing that where poor water quality is linked to agricultural land use, we have to take into account not only the spatial distribution of land use but the hydrology that connects land to water [1]. I have shown that not all land contributes equally to diffuse environmental pollution, yet most land management prescriptions remain blanket targets. We could do better. Further, I firmly believe that engaging the many different private and public stakeholders in land use, shown by the influence diagram, in the co-design of sustainable solutions will surely accelerate the benefits to be gained and build more lasting outcomes.

[1] Heathwaite (2010) Multiple stressors on water availability at global to catchment scales: understanding human impact on nutrient cycles to protect water quality and water availability in the long term. Freshwater Biology 55:uch of 241-257.

What we need to do better

There is no silver bullet answer to the challenge, no ready-made generic land use framework until the estimable ambitions of the Food, Farming and Countryside Commission are realised. But…since ‘Land Use Futures’ our ability to observe remotely (earth-observing technologies) and assimilate and understand data (data science and AI technologies) has grown markedly albeit we aren’t - yet - in a better place for understanding or agreeing what is land for? I think this is because we don’t engage fittingly with stakeholders in land at scales appropriate to the questions they are asking. That engagement might range from providing location data at a resolution that ensures local outcomes through community leadership e.g., natural flood management right up to national-level policy that brings natural capital considerations in decision-making. I also think we don’t spend sufficient time understanding the implications of decisions in one part of the land use system on another: in part because data and analytical techniques have constrained us until now. If we bring the data and the stakeholders together, we would be in a good place to make progress - as demonstrated by the Geospatial Commission’s National Underground Asset Register.

What next? The role for location data

The opportunities offered by dynamic (real-time) location data are one of the most exciting developments for visualising land use, especially if linked to AI/machine learning. We need to combine this opportunity with proactive decision-making (i.e. co-design with stakeholders) to get lasting outcomes. Brexit has many consequences for the UK, not least for the future of land use. That ‘farming is changing’ is of consequence not just for land; and not just for carbon but also for our future water supplies; the shape of the peri-urban economy of England; and for our health and wellbeing. Already, stakeholders are projecting their vision of what the future should look like. There is a role for the Geospatial Commission and its partners to ‘help the data talk’ by supporting the development of interoperable data platforms that could – at the very least – empower stakeholder discussions regarding trade-offs in land use. Such discussions could form the basis of futures thinking so that we can reflect on the consequences of decisions in one part of the land system for others – just as climate modellers have shaped our current thinking on Net Zero.

As set out, in the UK Geospatial Strategy, the Geospatial Commission is working with key stakeholders to identify a targeted approach to support delivery of a national land use framework.

The Geospatial Commission is keen to reflect and make available a wide range of views and approaches, including those that may stimulate debate. The Geospatial Commission does not necessarily endorse the content provided by guest contributors.

Follow this link to read more about the UK Geospatial Strategy.

Sign up to this blog to get an email notification every time we publish a new blog post.

1 comment

Comment by Peter Parslow posted on

It would seem wise that a future UK land use classification system learns from the experience of others. One way to do that is for the UK authorities to engage with the current project going on between UN Food & Agriculture Organisation, ISO and others on land use & land cover classification.

The UK has an easy way in to this, as both the current ISO projects are being lead by John Latham of Southampton University, nominated by BSI. He has already been in touch with Defra and the Geospatial Commission about this.

Note: my interest: I'm acting chair of the relevant BSI technical committee