The National Underground Asset Register (NUAR) is a government-led programme, which is creating a combined, standardised repository of buried asset data in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. That data is presented in a secure and interactive manner, which is available instantly to authorised users of the platform. Once complete, it will bring together data from over 600 organisations, both public and private, to give a comprehensive view of what lies beneath our feet.

This allows the locations of assets to be quickly and easily viewed on demand in a standard form and detailed, consistent information about them to be queried in the office and in the field. This will allow authorised users to safely and efficiently plan and execute works on and around buried networks.

Standardisation of the data in the service is critical to being able to present it in that combined and interactive manner. That standardisation is enabled by the NUAR Harmonised Data Model, which defines how the data describing the real-world assets and sites is structured, stored and retrieved.

Why did we bother with a Data Model?

Bringing together data from more than 600 organisations across a wide range of sectors in a manner that can be represented in a standard form is no easy task. To have any chance of success with this monumental task, a common language is required to describe the real-world concepts, objects and spaces, which comprise the subsurface domain that is relevant to NUAR.

This common language allows us to communicate information in a consistent manner across different organisations, sectors and geographies. This in turn allows us to have a standardised set of “joining instructions” for all eligible organisations who hold relevant data. That makes it easier to keep that data up to date, as it is constantly changing – when you are loading in a new set or a set of changes, having each iteration in the same structure makes life much easier.

A consistent framework for measuring data quality

As well as the practical advantages for the NUAR programme that a data model gives us, there are some broader considerations that make the hard work of developing a standardised data model worthwhile. We all know that there are real challenges in maintaining the accuracy, completeness and overall quality of data describing buried assets.

The industry has some unique circumstances contributing to these challenges, not least that significant amounts of UK infrastructure have been in the ground for many years, meaning that data has been captured across different eras with access to variable and evolving data capture and storage technologies. Much of the data we see now, even if in digital form, has often arrived at that state via several successive transformations from traditional media (e.g. linens, paper, microfiche, etc.).

Even if organisations now employ state of the art technology for data capture and storage, this cannot be applied everywhere and all at once to legacy data, so historical issues of data quality linger on.

From the above you can see that there is no single or simple fix for improving data quality. Therefore, several approaches and methods will need to be employed to effect meaningful improvement. Having a standardised data model as a target provides us for the first time with a framework for reporting on elements of data quality – such as completeness, consistency of representation, availability of metadata – in a consistent manner across different organisations, sectors and geographies. This presents huge opportunities for identification and discussion of areas that might benefit from scrutiny and targeted action to move the dial on data quality improvement.

Futureproofing; or modelling the world as we would like it to be

In the same vein, the NUAR Data Model is unapologetically aspirational in its design. What I mean by this is that it is designed explicitly to accommodate future developments in data capture technologies and practices.

At the present time, the capture of metadata describing elements of data quality, and methods of data capture, are relatively immature in the utilities sector (notwithstanding several organisations who are leading the way in this space), and there are other elements of data which are only sparsely captured and represented.

The NUAR Data Model attempts to provide a full suite of attribution for characteristics and metadata, which may not be routinely captured at present, but which is more likely to be available in future as technologies and capabilities evolve. In this way, the NUAR Data Model provides a home for data that may be captured in future even if not routinely captured at present.

Foundations for extensibility and open innovation

For all our attempts at futureproofing, nobody can confidently predict the future. There will undoubtedly be use cases and innovation in the future that we have not anticipated in the design of the NUAR Data Model.

One of the benefits of having a data model, however, is that while it may not cover all the bases right now, having a formally defined and managed model provides a solid foundation for these future developments. It is easier to extend a well-defined, well-governed foundational model to accommodate new knowledge and circumstances than it is to start again from scratch.

So, what exactly is a data model?

Notice that I have been talking above about the structure of the data, not the data itself. That is what a data model is: an abstract description of real-world concepts and objects, and the relationships between them.

A data model does not in itself contain actual data, so when I talk below about publishing the NUAR Data Model, we are not talking about publishing the actual data within NUAR. Access to that is, and will continue to be, carefully controlled and monitored, so we know who is accessing the data and for what purpose.

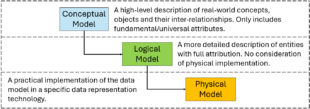

A data model can be defined at different levels of detail – from a high-level, abstract conceptual model, through more detailed logical models specialised for certain languages, communities and domains, down to physical models, which allow actual data to be loaded. These different levels are illustrated in the diagram below.

This hierarchy of conceptual-logical-physical models is important when we consider how the NUAR Data Model interacts with the latest developments in international standards.

Getting our hands dirty: the OGC MUDDI Model

Late in 2023 I wrote a blog on an event that the Open Geospatial Consortium (OGC) had run in London to evaluate various open standards that were under development. This included a description of the OGC Model for Underground Data Definition and Integration (MUDDI). I am very pleased to report that Part 1 of the MUDDI Standard (the Conceptual Model) has now been published on the OGC website as an approved OGC Standard.

The Geospatial Commission has been closely involved in the development of this standard through the NUAR programme, with active representation on the OGC Standards Working Group, and we are very proud of the fact that the NUAR Data Model is the first implementation of the MUDDI Conceptual Model in the world. The concepts, objects, relationships and minimal attribution represented in the MUDDI Conceptual Model can be found in the OGC documentation.

As you saw from the previous section, for a conceptual model to be usable for actual data it needs to have one or more Logical Models defined providing relevant detail and terminology for a given domain or use case. These Logical Models can ultimately be translated into a physical data store that can be used to store and retrieve compliant data. The next section describes what we have done for NUAR to provide an actual realisation of the MUDDI Conceptual Model.

Introducing the NUAR Data Model

The development of the NUAR Data Model has involved the definition of two logical models - one a generic representation of a “UK Excavation” logical model (or “profile” of the conceptual model) and another – the NUAR Harmonised Data Model - which contains further specific detail about how data is represented and managed in the NUAR platform. This latter model is ultimately translated into the physical database, which is populated with actual data and used by the NUAR platform to visualise it and allow users to interrogate the detailed attribution.

As well as being crucial to the ongoing development of the NUAR service, we think that these data models will be of interest to those working in the utilities sector, and those with a general interest in data modelling, standards and analytics. They illustrate some interesting and important concepts in the translation of a conceptual model into something usable.

This is why we have published artefacts describing the MUDDI UK Excavation Profile and the NUAR Harmonised Data Model under open terms in the public domain for use as community resources. You can find what we have published on GitHub.

It includes all sorts of supporting documentation about the principles, rationale and approach of the data model design, as well as XMI (XML Metadata Interchange) and SQL (Structured Query Language) encodings of the data models, allowing you to recreate the physical implementations as required. To re-iterate, none of these artefacts include any asset data – just the structures and relationships needed to store that data in a standardised manner, consistent with the OGC MUDDI Model.

These artefacts are being published under open terms for information, comment and general usage – we hope that you find them useful and informative. If you work with utilities or other subsurface data, we hope that these artefacts stimulate ideas or even provide a foundation for your work on the management, representation and improvement of your data.

We would love to hear your feedback on the work that we have done – whether suggestions for updates and improvements, or observations and the sharing of experiences in using and adapting them for your purposes. Please email geospatialcommission@dsit.gov.uk to get in touch.

What is next?

As noted above, these artefacts are being published for information, comment and general usage. There is no action required on the part of the NUAR community of asset owners and/or users as a result of this publication. Whist we would encourage asset owners to adopt the NUAR Harmonised Data Model for the submission of their data to NUAR, processes for the transformation of data for use in NUAR will be continuing as they are for the foreseeable future.

We will continue to iterate the NUAR Data Model itself and the artefacts that we publish. For instance, we will be working on data specifications and data submission encodings, initially in the GeoPackage format, that would allow organisations in future to experiment with generating data submissions that would be suitable for direct validation and ingestion into NUAR.

We are also looking at the development of a Data Maturity Model – effectively a toolkit for organisations to measure their level of compliance against the NUAR Harmonised Data Model. Watch this space for these developments, which we are looking forward to working on and sharing with you in due course.

In the meantime, I hope you have found this blog and the artefacts that we have published useful and thought-provoking, and we look forward to continuing the conversation on all things data, so please stay in touch via our social media channels or by email at geospatialcommission@dsit.gov.uk.

Scotland already benefits from a similar system called Scottish Community Apparatus Data Vault (or Vault for short), which is operated by the Scottish Roadworks Commission. The NUAR programme has worked closely with colleagues in Scottish Government to ensure alignment.